Like many Americans, I began this October indulging in Halloween traditions, including a marathon in which I watch a horror movie every day of the month.

Like most Americans, and people all over the world, I also began this October in mourning, shocked by the news that gunman Stephen Paddock killed 59 Las Vegas concert attendees and wounded hundreds more.

This month, in the wake of such a horrific event, in a country in which such attacks are growing increasingly common, the question is unavoidable: Why choose to watch terrible or scary things on a movie screen when we see them all over the news? What’s the point of horror movies when the world seems filled with unavoidable horror?

It’s a fair question—even a necessary one. But I do think such films serve a purpose, for many fans. Especially in times like these, in which fear and violence have become an all too familiar part of our daily lives.

Alongside perennial favorites like John Carpenter’s The Thing and Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein, my lineup this year includes the 1968 film Targets, written and directed by Peter Bogdanovich. Targets tells two stories, which converge in the climax. The first features aged monster movie star Byron Orlok (Boris Karloff, playing a disgruntled version of himself) as he prepares for one last promotional appearance at the premier of his final film, The Terror (an actual re-purposed Roger Corman picture, staring Karloff and Jack Nicholson). The other half follows Bobby Thompson (Tim O’Kelly), a nondescript suburbanite who succumbs to his “funny thoughts” and commits three mass shootings, culminating at the drive-in theater debuting Orlok’s movie.

Inspired in part by a 1966 shooting at the University of Texas, Targets has always been a difficult film, but the recent increase in gun violence gives it new immediacy. No one watching Bobby murder moviegoers can help but think about attacks at showings of The Dark Knight Rises and Trainwreck.

In light of this collision of fictional and actual violence, one may reasonably ask, “Why? Why watch horror movies when the real world is already so horrific?”

The short answer is the most honest: scary movies are fun. The macabre always carries a certain allure, and while movie watching engages the death drive less directly than, say, skydiving, the same principle is at work. Films allow us to tease danger from a place of safety.

Despite its subject matter, Targets reflects this sense of fun with its Orlok storyline. Karloff is thoroughly delightful as an outdated actor whose bitterness cannot diminish his charm. The movie relishes in his performance, most obviously when Orlok recites the W. Somerset Maugham piece “The Appointment in Samarra.” The camera slowly pushes in on the narrating Karloff, his baritone accentuating the story’s fatalistic menace. So powerful is the delivery that it halts his heretofore busy companions, silencing even a motor-mouthed disc jockey. The story might be about the inescapability of death, but they cannot help but indulge in the pleasure of the telling and the tale.

Part of the listeners’ enjoyment comes from the way they consume it as a group, pulled together by Orlok’s creepy charisma, foreshadowing the crowds who gather to watch The Terror in the film’s climax. The communal element here reminds us that the fun of horror relies, in part, on the way we watch with one another, as part of an audience. Other people make us feel safe.

Clichés about lovers grasping each other in terror or people shouting out obvious advice to onscreen characters have long dogged the genre, but such behavior can be traced all the way back to classical Greek drama. Building on Aristotle’s theory of catharsis among audience members, Friedrich Nietzsche’s essay The Birth of Tragedy argues that tragic dramas allow audiences to “gaze into the terrors of individual existence,” to feel primordial existence’s “unbounded greed and lust for being.” But the awareness of appearances, knowing that that the performance is fake, overwhelms the audience in a collective response: “Despite fear and pity, we are happily alive, not as individuals, but as the one living being, with whose procreative lust we have become one.” The images on stage fill us with dread, but the realization that we see it together gives us strength to overcome the traumatic lives and meaningless deaths unfolding before our eyes.

As a genre that celebrates visceral audience reaction, horror continues tragedy’s ability to bind people together against fear. Group engagement has always been part of horror culture, from people rioting outside 1921 showings of The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari to gossip about people fainting and sobbing during screenings of The Texas Chainsaw Massacre to the audible sighs and cheers when the protagonist’s best friend emerges in this year’s Get Out.

Friends banding together against monsters also play an important role in 2017’s other horror hit, the Andy Muschietti-directed adaptation of Stephen King’s It. The titular monster is a cosmic entity that feeds on dread by taking the form of its victims’ anxieties. The adolescent heroes know they can defeat the monster by refusing to be afraid, but they cannot do that alone; they need support from one another to overcome the things that scare them.

It demonstrates that community provides comfort against terror, but also drives home the fact that this shared solace can only be found when we confront horror in some way. To face our fears, our fears need a face. Scary movies provide that for us, giving monstrous form to individual and social anxieties. Thus, concerns about atomic energy manifest in giant lizards, and worries about suburban safety become Michael Myers and Freddy Krueger.

Targets plays with this idea by giving evil an utterly innocuous face. O’Kelly plays Bobby with a goofy grin and an “aw shucks” demeanor. He radiates wholesomeness, from the way he calls his father “sir” to his affinity for Baby Ruth bars. Initially, the movie even lets his gun collecting hobby seem innocent, a form of all-American bonding between father and son. When a shop owner tells Bobby “You’ve got an honest face,” he speaks for the entire audience.

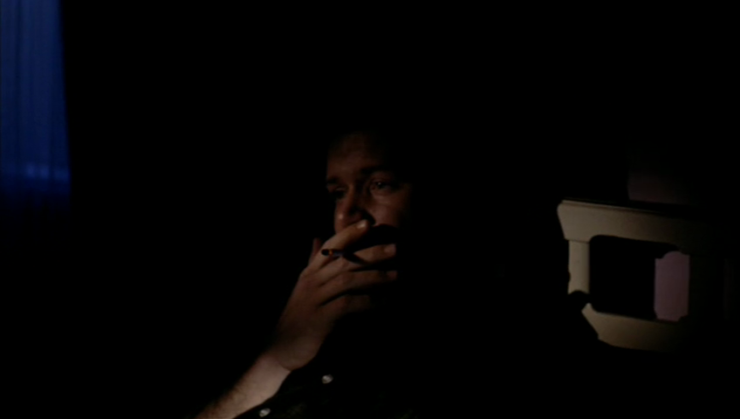

Targets hides that face in just one scene, on the night before Bobby’s killing spree. Bogdanovich and cinematographer László Kovács keep Bobby’s expression in shadow, limiting light to the glow of his cigarette. Even when capturing the point of view of his wife Eileen, closing in for a goodnight kiss, Bobby’s face is distorted, out of focus. In the next scene, the camera takes Bobby’s perspective as Eileen attempts a good morning kiss, which he returns with a gunshot to her stomach—his first of many kills.

Unlike Orlok, who vacillates between amusingly cantankerous with his friends and theatrically malevolent on screen, Bobby acts almost devoid of affect, and the movie refuses to infuse his killing with any sense of melodrama. It keeps audiences removed from the murders, either displaying reactions through Bobby’s long-range site or cutting quickly between images of his victims.

Where scenes from The Terror feature Gothic touches like a castle illuminated by lightning and close-ups of cawing crows, Bobby’s actions are dull. After his first killings—Eileen, his mother, and an unlucky grocery boy—the camera moves across his living room floor, lingering on banal objects (a beige carpet, a slipper, a dresser), before panning up to a short manifesto that concludes, “I know they will get me, but there will be more killing before I die.” On the soundtrack we hear only the noises common to a quiet suburban day: birds chirping, kids playing, a car starting up and driving away.

Earlier in the film, Orlok complained that he cannot scare people living in an age of random violence; “My kind of horror isn’t horror anymore,” he laments. “No one’s afraid of a painted monster.” The contrast in Targets between Orlok and Bobby seems to prove that point, and the point of those who question the morality of the genre: real killers should haunt us far more than celluloid ghouls.

But that reading fails to consider the key moment in the final sequence, in which Orlok, having caught sight of the shooter behind the screen, confronts Bobby. As he realizes who approaches him, Bobby looks back and forth between Orlok in the movie, walking across the screen as The Terror’s murderous Baron, and the real Orlok, drawing closer. The terrified Bobby fires at Orlok, but misses the older man, who easily knocks the gun from his hand and slaps the gunman until he lies in the fetal position. Stunned, Orlok asks, “Is that what I was so afraid of?”

When I watch horror movies, I find myself asking the same question. G.K. Chesterton famously said that a fairy tale does not produce in a child a fear of dragons, but rather “what the fairy tale provides for him is a St. George to kill the dragon.” Horror movies do this as well. They show me what I fear—not simply monsters or supernatural evils, but the terror of random, inexplicable violence; a stranger with a seemingly friendly, innocuous face committing senseless murders without reason or remorse. And while these movies don’t always give me a St. George or other hero to somehow manufacture a happy ending, they do allow me to look away from the images and back at the people watching with me, collectively facing their fears in the dark of the theater. Their presence, the shared experience of communal anxiety and catharsis, the fandoms and communities and relationships we build and maintain even during the darkest times—all of this is a source of comfort to me. Not an escape from the horror of everyday life, but a comfort all the same.

Joe George‘s writing has appeared at Think Christian, FilmInquiry, and is collected at joewriteswords.com. He hosts the web series Renewed Mind Movie Talk and tweets nonsense from @jageorgeii.